Okinawa Prefecture

Okinawa Prefecture

沖縄県 | |

|---|---|

| Name transcription(s) | |

| • Japanese | 沖縄県 |

| • Rōmaji | Okinawa-ken |

| • Okinawan | Uchināchin |

| Anthem: "Song of Okinawa Prefecture" (沖縄県民の歌, Okinawa kenmin no uta) | |

| Coordinates: 26°30′N 128°0′E / 26.500°N 128.000°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Kyushu |

| Island | Okinawa, Daitō, Miyako, Yaeyama, and Senkaku |

| Capital | Naha |

| Subdivisions | Districts: 5, Municipalities: 41 |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Denny Tamaki |

| Area | |

• Total | 2,281 km2 (881 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 44th |

| Population (September 1, 2024) | |

• Total | 1,466,944 |

| • Rank | 29th |

| • Density | 640/km2 (1,700/sq mi) |

| GDP | |

| • Total | JP¥ 4,633 billion US$ 42.5 billion (2019) |

| ISO 3166 code | JP-47 |

| Website | www |

| Symbols of Japan | |

| Bird | Okinawa woodpecker (Sapheopipo noguchii) |

| Fish | Banana fish (Pterocaesio diagramma, "takasago", "gurukun") |

| Flower | Deego (Erythrina variegata) |

| Tree | Pinus luchuensis ("ryūkyūmatsu") |

Okinawa Prefecture (Japanese: 沖縄県/おきなわけん, Hepburn: Okinawa Ken, Okinawan: 沖縄県, romanized: Uchināchin[2]) is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan.[3] It consists of three main island groups—the Okinawa Islands, the Sakishima Islands, and the Daitō Islands—spread across a maritime zone approximately 1,000 kilometers east to west and 400 kilometers north to south. Despite a modest land area of 2,281 km² (880 sq mi), Okinawa’s territorial extent over surrounding seas makes its total area nearly half the combined size of Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu.[4] Of its 160 islands, 49 are inhabited.[5] The largest and most populous island is Okinawa Island, which hosts the capital city, Naha, as well as major urban centers such as Okinawa, Uruma, and Urasoe.[6] The prefecture has a subtropical climate, characterized by warm temperatures and high rainfall throughout the year.[7] The indigenous inhabitants are the Ryukyuans, who also reside in the nearby Amami Islands of Kagoshima Prefecture.

Okinawa was historically part of the independent Ryukyu Kingdom, which unified the Ryukyu Islands in 1429. In 1609, the kingdom was invaded by the Japanese Satsuma Domain and subsequently became a vassal state under Satsuma's indirect control. Despite this, the Ryukyu Kingdom retained considerable autonomy and continued to maintain formal tributary relations with both Ming and Qing China as well as the Satsuma Domain.[8] During Japan’s Edo period, while both China and Japan practiced isolationist policies, Ryukyu’s strategic location enabled it to flourish through intermediary trade.[8] Following the Meiji Restoration, the Ryukyu Kingdom was restructured as the Ryukyu Domain, the last domain of the Han system, in 1872, and was formally annexed by Japan as Okinawa Prefecture in 1879.[9] In contrast, the Amami Islands, which are geographically part of the Ryukyu Archipelago, had already been separated from the Ryukyu Kingdom and incorporated into Kagoshima Prefecture. [10] Okinawa was occupied by the United States during the Allied occupation of Japan after World War II and was governed by the Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands from 1945 to 1950 and Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands from 1950 until the prefecture was returned to Japan in 1972. Okinawa comprises just 0.6 percent of Japan's total land mass, but about 26,000 (75%) of United States Forces Japan personnel are assigned to the prefecture; the continued U.S. military presence in Okinawa is controversial.[11][12]

Due to its distinct historical trajectory, Okinawa maintains unique cultural characteristics, including its own languages, cuisine, and customs that differ significantly from mainland Japan. The islands are also the birthplace of karate.[9] Economic activity in Okinawa is predominantly service-based due to geographical constraints limiting agriculture and manufacturing. There is also a longstanding independence movement among some Okinawans, rooted in cultural identity and political dissatisfaction with the continued presence of U.S. military bases.[13]

History

[edit]

| History of Ryukyu |

|---|

|

Prehistoric and Ancient History

[edit]The prehistoric history of Okinawa differs significantly from that of mainland Japan. Prior to written records, it is generally divided into two periods: the Paleolithic era and the Shellmidden period (Kaizuka period).[14][14]: 14 The earliest evidence of human activity in Okinawa includes the Yamashita Cave Man, dating back approximately 32,000 years, and the Minatogawa Man from around 18,000 years ago.[14]: 14 In 2012, the world's oldest known fishhook was discovered in the Sakitari Cave site in Nanjo City, Okinawa Prefecture.[15]

The Shellmidden period corresponds roughly to the Jōmon through Heian period in mainland Japan,[14]: 16 and is separated from the Paleolithic era by a roughly 10,000-year gap.[14]: 26 In the early Shellmidden period, pottery from the southern Ryukyu Islands was highly similar to that of the Jōmon pottery of mainland Japan. However, during the middle period, Okinawan pottery began to develop distinct local characteristics. By the later Shellmidden period, Okinawan pottery again showed strong influence from Kyushu.[14]: 26 During this later phase, large-scale coastal settlements began to appear, and coins from China’s Tang dynasty, including the Kaiyuan Tongbao, were discovered—indicating contact between Okinawa and the Chinese mainland during this period.[16]: 17

In contrast to the Shellmidden culture of Okinawa Island, which was influenced primarily by mainland Japan, the prehistoric cultures of the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands were shaped more significantly by southern cultures, including those from the Philippines.[16]: 19

Gusuku and Sanzan Periods

[edit]

From the 12th century onward, Okinawa entered the Gusuku period, characterized by the development of an agrarian society. During this time, populations moved from coastal dunes to more fertile limestone plateaus, leading to significant population growth and the beginnings of international trade.[16]: 24 Local chieftains, known as Aji, constructed fortified residences called Gusuku to protect their territories and expand their influence through foreign trade.[16]: 26 Gusuku sites are found throughout the Ryukyu Islands, from the Amami Islands in the north to the Yaeyama Islands in the south, with estimates ranging from 300 to 400 sites in total. Early Gusuku were generally small, covering about 1,000 square meters, but larger fortresses appeared in later periods.[14]: 48

By the 14th century, Okinawa Island was divided into three polities, marking the beginning of the Sanzan period. These were the Kingdom of Hokuzan, centered at Nakijin Castle in the north; the Kingdom of Chūzan, centered at Urasoe Castle in the central region; and the Kingdom of Nanzan, centered at Ōzato Castle in the south.[16]: 26

According to official histories compiled by the royal government in Shuri—such as the Chūzan Seikan, Chūzan Seifu, and Kyūyō—the first royal lineage of Ryukyu was the legendary Tenson dynasty. After internal conflict during its 25th generation, a local Aji named Shunten from Urasoe was supported by the people, quelled the unrest, and was crowned as the first king of the Ryukyu Kingdom.[16]: 30 However, these early historical accounts are heavily mythologized, and even if Shunten was a real historical figure, he likely ruled only the Urasoe area as an Aji.[16]: 30 The Shunten dynasty lasted for three generations before being overthrown by the Eiso dynasty, which in turn was replaced by the Satto dynasty after four generations. By this time, Okinawa Island had effectively split into the three kingdoms of Hokuzan, Chūzan, and Nanzan.[16]: 34

In 1372, the Ming dynasty of China dispatched an envoy, Yang Zai, to the Kingdom of Chūzan, requesting the king, Satto, to enter into a tributary relationship. Satto agreed, and soon after, the kings of Nanzan (Chōsatto) and Hokuzan (Hanishi) also began paying tribute to the Ming court, bringing all three kingdoms into the Chinese tributary system.[16]: 36

In 1406, the Aji of Sashiki, Shō Hashi, overthrew King Bunei of the Satto dynasty and installed his father, Shō Shishō, as king, establishing the First Shō Dynasty.[16]: 42 In 1416, Shō Hashi capitalized on dissatisfaction among the Aji of Hokuzan with their king, Hananchi, and conquered the kingdom. The Kingdom of Nanzan, plagued by internal conflict under the rule of Tarumoi, was defeated by Shō Hashi in 1429, completing the unification of Okinawa Island under the Chūzan Kingdom.[16]: 42

Ryukyu Kingdom Period

[edit]

The First Shō Dynasty experienced political instability due to the early deaths of several kings. After the death of the fifth king, Shō Kinpuku, a succession dispute known as the Shirii-Tumui rebellion broke out. Order was eventually restored when Shō Taikyū ascended as the sixth king.[16]: 45 During his reign, another major conflict, the Gosamaru–Amawari rebellion, occurred, but Shō Taikyū was able to suppress it.[16]: 46 His successor, King Shō Toku, was known as a tyrant. After his death, a coup led by royal officials installed the high-ranking bureaucrat Kanemaru as king.[14]: 89 Kanemaru took the royal name Shō En, founding the Second Shō Dynasty.[16]: 48

Under the rule of the third king of the dynasty, Shō Shin, a centralized administration was firmly established. Shō Shin relocated powerful regional chieftains (Aji) to the capital of Shuri and appointed state officials to govern the provinces directly. The territorial extent of the Ryukyu Kingdom also expanded, covering the area from the Amami Islands in the north to the Yaeyama Islands in the south.[16]: 48 Culturally, this era was a golden age for the kingdom, with significant development in the arts, religion, and architecture.[16]: 53

By actively participating in the tribute system with the Ming dynasty, the Ryukyu Kingdom received preferential treatment and became a key intermediary trading hub in East Asia. Many of the tribute goods presented to China originated from Japan, while Chinese goods were exported to Japan through Ryukyu.[16]: 56 Southeast Asia, China, and Japan were Ryukyu’s primary trade partners,[16]: 59 and the kingdom also maintained trade with the Korean Peninsula.[16]: 58 However, Ryukyu’s significance as a trade hub declined in the 16th century with the Age of Discovery, as Portuguese and Spanish merchants entered East Asia, and China gradually relaxed its maritime prohibition policies.[16]: 60

The Miyako Islands and Yaeyama Islands had long been politically fragmented. In 1474, local strongman Nakasone Toyomiya of Miyako Island submitted to the Ryukyu Kingdom, bringing the island under centralized control.[16]: 64 In 1500, Ryukyuan forces defeated Oyake Akahachi, the ruler of Ishigaki Island.[16]: 66 In 1522, Nakasone Toyomiya conquered Yonaguni Island, completing the unification of the Yaeyama Islands under Ryukyuan rule.[16]: 68 The Amami Islands in the north also came under Ryukyuan control by 1466.[16]: 70

In 1609, the Shimazu clan of the Satsuma Domain invaded the Ryukyu Kingdom in what is known as the Invasion of Ryukyu. King Shō Nei surrendered, and the kingdom became a vassal state under Satsuma’s control. The Amami Islands were ceded to Satsuma as part of the settlement.[14]: 133 While Ryukyu was partially integrated into Japan’s feudal han system, it continued to function as a nominally independent kingdom and maintained its tributary relationship with China.[16]: 85 Ryukyuan sovereignty was maintained since complete annexation would have created a conflict with China. The Satsuma clan earned considerable profits from trade with China during a period in which foreign trade was heavily restricted by the shogunate. Although Satsuma maintained strong influence over the islands, the Ryukyu Kingdom maintained a considerable degree of domestic political freedom for over two hundred years.[17]

In the mid-17th century, the Ryukyuan reformer Haneji Chōshū implemented significant political and social reforms promoting pro-Japanese policies.[14]: 152 In the mid-18th century, Sai On, a statesman and scholar, continued these reforms and greatly improved the internal administration of the kingdom.[16]: 101

In 1816, two British ships visited Ryukyu but made no demands for trade or missionary activity.[16]: 131 In 1844, France became the first European country to officially request trade with Ryukyu.[16]: 132 In 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry of the United States East India Squadron stopped in Ryukyu prior to his negotiations with the Tokugawa shogunate in Japan.[16]: 138

First Okinawa Prefecture Period

[edit]

Following the Meiji Restoration, Japan began its modernization process by abolishing the han system and establishing prefectures in 1871. That same year, the Mudan Incident occurred when a Ryukyuan ship drifted to Taiwan and its crew was killed by local indigenous people. This event became a pretext for Japan to assert control over the Ryukyu Kingdom. In 1872, Japan reclassified the kingdom as the Ryukyu Domain, a move known as the Ryukyu Disposition. To avoid backlash from the Qing dynasty and Ryukyuan royalty, the Meiji government initially designated Ryukyu as a "domain" rather than a "prefecture", a designation that had already been abolished in mainland Japan.[16]: 147

In 1874, another Ryukyuan shipwreck incident led to the Taiwan Expedition of 1874 (the Botan War), in which Japan dispatched troops to Taiwan. During post-conflict negotiations, the Qing acknowledged Japan’s actions as “a righteous act of protecting its people.” Japan interpreted this as de facto recognition of Ryukyu as Japanese territory and subsequently ordered the Ryukyu Domain to cease its tribute missions to China. This triggered internal division within the Ryukyuan court between pro-Japan and pro-China factions.[16]: 151

In March 1879, the Japanese government officially abolished the Ryukyu Domain and established Okinawa Prefecture, relocating King Shō Tai to Tokyo. Some Ryukyuan nobles and civilians fled to China and appealed to the Qing government to restore the Ryukyu Kingdom. Resistance in the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands was especially strong, culminating in the Kōchi Incident, in which locals killed a Japanese interpreter. However, the rebellion was eventually suppressed.[16]: 151

The Qing dynasty invited former U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant to mediate the dispute. Grant proposed a compromise in which the Okinawa Islands would go to Japan, while the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands would be ceded to China. The Qing countered with a plan that would return the Ryukyu Kingdom to the Okinawa Islands, assign the Amami Islands to Japan, and annex the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands to China. Ultimately, the negotiations failed. After the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), the Qing ceded Taiwan to Japan and lost influence in the region, silencing calls for the restoration of Ryukyu.[16]: 154

In the early years of direct Japanese rule, a policy known as the Old Customs Preservation Policy (旧慣温存政策, Kyūkan Onzon Seisaku) was implemented, maintaining Ryukyuan land and tax systems, which slowed Okinawa’s modernization.[16]: 156 After the First Sino-Japanese War, Japan replaced this policy with an assimilation strategy, accelerating Okinawa's Japanization. However, Okinawa's strategic and economic importance declined, particularly after Taiwan became Japan's new southern frontier and sugar-producing center.[16]: 161

In the 20th century, Japan undertook major land reforms and prioritized sugar production in Okinawa, though economic development remained far behind mainland Japan.[16]: 164 Transportation infrastructure also modernized, with new roads, railways, and ferry routes to the Japanese mainland established in the early 1900s.[16]: 182 During the early Taishō era, Okinawa briefly prospered as sugar prices soared due to World War I.[16]: 187 However, by the late Taishō and early Shōwa era, the Great Depression struck, causing widespread famine. Many impoverished farmers resorted to eating the toxic cycad plant to survive, in what became known as the “Cycad Hell” (Sotetsu Jigoku (蘇鉄地獄)).[18]: 153 Many Okinawans migrated to mainland Japan or abroad. Between 1923 and 1930, Okinawans accounted for 10% of all Japanese emigrants. Remittances from overseas workers contributed 40% to 65% of the prefecture's annual budget.[16]: 190

In the 1930s, Japan increasingly pursued a path of militarism. By the 1940s, Okinawa Prefecture was integrated into the wartime regime. The government enforced standard Japanese language use and replaced traditional Ryukyuan name pronunciations with Japanese ones as part of a broader imperial assimilation policy.[16]: 209

In 1943, the Japanese military began seizing land in Okinawa to build airbases. In 1944, the 32nd Army was stationed in Okinawa, requisitioning resources from civilians and initiating evacuations to mainland Japan and Taiwan.[16]: 214 In August 1944, the evacuation ship Tsushima Maru, carrying about 1,700 evacuees, was sunk by an American submarine, resulting in 1,476 deaths.[16]: 215 In October that same year, Naha was bombed in the 10-10 air raids, destroying 90% of the city.[19]

In March 1945, the U.S. military landed in the Ryukyu Islands, initiating the Battle of Okinawa. The battle was notoriously intense and destructive, known as the “Typhoon of Steel” (鉄の暴風).[18]: 215 The U.S. military suffered 12,520 deaths, while Japanese casualties were significantly higher, with 94,136 killed—including 28,228 Okinawan conscripts. Civilian losses were also devastating. Not only were civilians caught in the crossfire, but Japanese troops also executed civilians on suspicion of espionage and forced mass suicides. Approximately 94,000 civilians died in the battle, with total military and civilian deaths reaching around 200,000.[16]: 229 [16]: 230

Postwar Disposition Disputes

[edit]During World War II, the Allied powers engaged in multiple rounds of discussions regarding the postwar status of the Ryukyu Islands. At the Cairo Conference in 1943, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt proactively raised the issue of Ryukyu’s sovereignty, suggesting that China might administer the islands after the war. However, Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek responded only cautiously, proposing instead a joint occupation and international trusteeship. As a result, the Cairo Declaration made no explicit reference to the Ryukyus, instead stating that territories such as Taiwan and the Pescadores—seized by Japan—should be returned to China. Historians believe Chiang hesitated because he was unsure whether Roosevelt’s offer was sincere or a diplomatic probe, and because the wartime Nationalist government relied heavily on American support and wished to avoid a territorial dispute.

As the Pacific War progressed, the U.S. military increasingly emphasized the strategic importance of the Ryukyus. In 1944, some U.S. officials proposed exclusive control of the islands to serve as a bulwark against Soviet expansion and threats from the Asian mainland. Roosevelt reportedly expressed to Joseph Stalin his support for returning the Ryukyus to China, but no formal agreements emerged from the Cairo, Yalta, or Potsdam meetings. The Potsdam Declaration stated only that Japanese sovereignty would be limited to the islands of Honshu, Kyushu, Shikoku, and Hokkaido, while other territories—including the Ryukyus—would be subject to future decisions by the Allied powers.[20][21]

After the war, the Nationalist government of China recognized the strategic value of the Ryukyu Islands and proposed a joint trusteeship with the United States for a period of five to ten years. Later proposals included allowing the U.S. to establish bases on some islands, indicating a willingness to compromise and an understanding that the U.S. would not readily transfer sovereignty to China. Chinese domestic opinion was divided: some called for an independent Ryukyuan state, others demanded the full incorporation of the Ryukyus into Chinese territory. Most emphasized the islands’ strategic importance as a buffer zone and argued they should not fall into the hands of another power.[20]

In 1946, the United States Department of State advocated for the return of the Ryukyus to Japan, citing anti-expansion principles and concerns over economic burdens. In contrast, the U.S. military proposed that the islands be designated as a "strategic trust territory," with Okinawa Island declared a "strategic area." Military leaders argued that the high cost of American lives during the Battle of Okinawa justified permanent military governance as compensation for their sacrifice. After internal debate, the plan was formalized in SWNCC 59/1, which proposed placing Okinawa under U.S. military administration rather than returning it to Japan, using trusteeship arrangements to sidestep sovereignty issues. The directives SCAPIN-677 and SCAPIN-841 established the legal and administrative basis for U.S. jurisdiction south of the 29th parallel north, forming the framework for postwar American control.[21]

U.S. administration (1945–1972)

[edit]On April 1, 1945, the U.S. Army and Marine Corps launched an invasion of Okinawa with approximately 185,000 troops. They encountered determined and intense resistance from the Japanese defenders. During the subsequent fighting, approximately one-third of Okinawa's civilian population lost their lives. The dead, of all nationalities, are commemorated at the Cornerstone of Peace.[22]

After the end of World War II, the United States set up the United States Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands, which later became the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands. The United States established numerous military bases on the Ryukyu Islands during its 27-year-long "trusteeship rule".[23]

Continued U.S. military buildup

[edit]During the Korean War, B-29 Superfortresses flew bombing missions over Korea from Kadena Air Base on Okinawa. The military buildup on the island during the Cold War increased a division between local inhabitants and the American military. Under the 1952 Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan, United States Forces Japan (USFJ) have maintained a large military presence.

During the mid-1950s, the U.S. seized land from Okinawans to build new bases or expand currently existing ones. According to the Melvin Price Report, by 1955, the military had displaced 250,000 residents.[24]

Secret U.S. deployment of nuclear weapons

[edit]Since 1960, the U.S. and Japan have maintained an agreement that allows the U.S. to secretly bring nuclear weapons into Japanese ports.[25][26][27] The Japanese people tended to oppose the introduction of nuclear arms into Japanese territory[28] and the Japanese government's assertion of Japan's non-nuclear policy and a statement of the Three Non-Nuclear Principles reflected this popular opposition. Most of the weapons were alleged to be stored in ammunition bunkers at Kadena Air Base.[29] Between 1954 and 1972, 19 different types of nuclear weapons were deployed in Okinawa, but with fewer than around 1,000 warheads at any one time.[30] In fall 1960, U.S. commandos in Green Light Teams secret training missions carried small nuclear weapons on the east coast of Okinawa Island.[31]

Vietnam War

[edit]

Between 1965 and 1972, Okinawa was a key staging point for United States in its military operations directed towards North Vietnam. Along with Guam, it presented a geographically strategic launch pad for covert bombing missions over Cambodia and Laos.[32] Anti-Vietnam War sentiment became linked politically to the movement for reversion of Okinawa to Japan. In 1965, the U.S. military bases, earlier viewed as paternal post war protection, were increasingly seen as aggressive. The Vietnam War highlighted the differences between United States and Okinawa but showed a commonality between the islands and mainland Japan.[33]

As controversy grew regarding the alleged placement of nuclear weapons on Okinawa, fears intensified over the escalation of the Vietnam War. Okinawa was perceived by some inside Japan as a potential target for China, should the communist government feel threatened by United States.[34] American military secrecy blocked any local reporting on what was actually occurring at bases such as Kadena Air Base. As information leaked out, and images of air strikes were published, the local population began to fear the potential for retaliation.[33]

Political leaders such as Makoto Oda, a major figure in the Beheiren movement (Foundation of Citizens for Peace in Vietnam), believed that the return of Okinawa to Japan would lead to the removal of U.S. forces, ending Japan's involvement in Vietnam.[35] In a speech delivered in 1967, Oda was critical of Prime Minister Eisaku Satō's unilateral support of America's war in Vietnam, claiming "Realistically we are all guilty of complicity in the Vietnam War".[35] The Beheiren became a more visible anti-war movement on Okinawa as the American involvement in Vietnam intensified. The movement employed tactics ranging from demonstrations to handing leaflets to soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines directly, warning of the implications for a third World War.[36]

The U.S. military bases on Okinawa became a focal point for anti-Vietnam War sentiment. By 1969, over 50,000 American military personnel were stationed on Okinawa.[37] United States Department of Defense began referring to Okinawa as the "Keystone of the Pacific". This slogan was imprinted on local U.S. military license plates.[38]

In 1969, chemicals leaked from the U.S. storage depot at Chibana in central Okinawa, under Operation Red Hat. Evacuations of residents took place over a wide area for two months. Even two years later, government investigators found that Okinawans and the environment near the leak were still suffering because of the depot.[39]

On May 15, 1972, the U.S. government returned the islands to Japan following the signing of the 1971 Okinawa Reversion Agreement.[40]

Post-reversion history (1972–present)

[edit]

The 1995 kidnaping, beating, and rape of a 12-year-old girl by three U.S. servicemen triggered widespread protests in Okinawa. Reports by the local media of accidents and crimes committed by U.S. servicemen have reduced the local population's support for the U.S. military bases. A strong emotional response has emerged from certain incidents.[41]

Documents declassified in 1997 proved that both tactical and strategic weapons have been maintained in Okinawa.[39] In 1999 and 2002, the Japan Times and the Okinawa Times reported speculation that not all weapons were removed from Okinawa.[42][43] On October 25, 2005, after a decade of negotiations, the governments of the U.S. and Japan officially agreed to move Marine Corps Air Station Futenma from its location in the densely populated city of Ginowan to the more northerly and remote Camp Schwab in Nago by building a heliport with a shorter runway, partly on Camp Schwab land and partly running into the sea.[44] The move is partly an attempt to relieve tensions between the people of Okinawa and the Marine Corps.

Despite Okinawa prefecture constituting only 0.6% of Japan's land surface, in 2006 75% of all USFJ bases were located on Okinawa, occupying 18% of the main island.[44][45]

In a poll conducted by The Asahi Shimbun in May 2010, 43% of the Okinawan population wanted the complete closure of the U.S. bases, 42% wanted reduction, and 11% wanted to maintain the status quo. Okinawan feelings about the U.S. military are complex.[46]

In early 2008, U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice apologized after a series of crimes involving American troops in Japan, including the rape of a young girl of 14 by a Marine on Okinawa. The U.S. military imposed a temporary 24-hour curfew on military personnel and their families to ease the anger of local residents.[47] Some cited statistics that the crime rate of military personnel is consistently less than that of the general Okinawan population.[48] However, some criticized the statistics as unreliable, since violence against women is under-reported.[49] Between 1972 and 2009, U.S. servicemen committed 5,634 criminal offenses, including 25 murders, 385 burglaries, 25 arsons, 127 rapes, 306 assaults and 2,827 thefts.[50] Yet, per Marine Corps Installations Pacific data, U.S. service members are convicted of far fewer crimes than local Okinawans.[51]

In 2009, a new Japanese government came to power and froze the U.S. forces relocation plan but in April 2010 indicated their interest in resolving the issue by proposing a modified plan.[52] A study done in 2010 found that the prolonged exposure to aircraft noise around the Kadena Air Base and other military bases cause health issues such as a disrupted sleep pattern, high blood pressure, weakening of the immune system in children, and a loss of hearing.[53]

In 2011, it was reported that the U.S. military—contrary to repeated denials by The Pentagon—had kept tens of thousands of barrels of Agent Orange on the island. The Japanese and American governments have angered some U.S. veterans, who believe they were poisoned by Agent Orange while serving on the island, by characterizing their statements regarding Agent Orange as "dubious", and ignoring their requests for compensation. Reports that more than a third of the barrels developed leaks have led Okinawans to ask for environmental investigations, but as of 2012[update] both Tokyo and Washington refused such action.[54] Jon Mitchell has reported concern that the U.S. used American Marines as chemical-agent guinea pigs.[55]

On September 30, 2018, Denny Tamaki was elected as the next governor of Okinawa prefecture, after a campaign focused on sharply reducing the U.S. military presence on the island.[56]

Marine Corps Air Station Futenma relocation

[edit]In 2006, some 8,000 U.S. Marines were removed from the island and relocated to Guam.[57] The move to Marine Corps Base Camp Blaz was expected to be completed in 2023 but as of 1 January 2025 is still in process. Japan paid for a majority of the cost to construct the new base.[58][59] The U.S. still maintains Air Force, Marine, Navy, and Army military installations on the islands. These bases include Kadena Air Base, Camp Foster, Marine Corps Air Station Futenma, Camp Hansen, Camp Schwab, Torii Station, Camp Kinser, and Camp Gonsalves. The area of 14 U.S. bases are 233 square kilometres (90 sq mi), occupying 18% of the main island. Okinawa hosts about two-thirds of the 50,000 American forces in Japan although the islands account for less than one percent of total lands in Japan.[45]

Suburbs have grown towards and now surround two historic major bases, Futenma and Kadena. A sizable portion of the land used by the U.S. military is Camp Gonsalves in the north of the island.[60] On December 21, 2016, 10,000 acres of Camp Gonsalves were returned to Japan.[61] On June 25, 2018, Okinawa residents held a protest demonstration at sea against scheduled land reclamation work for the relocation of a U.S. military base within Japan's southernmost island prefecture. A protest gathered hundreds of people.[62]

Since the early 2000s, Okinawans have opposed the presence of American troops helipads in the Takae zone of the Yanbaru forest near Higashi and Kunigami.[63] This opposition grew in July 2016 after the construction of six new helipads.[64][65]

Geography

[edit]Major islands

[edit]

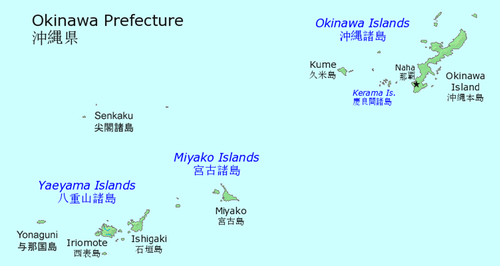

The islands comprising the prefecture are the southern two thirds of the archipelago of the Ryūkyū Islands (琉球諸島, Ryūkyū-shotō). Okinawa's inhabited islands are typically divided into three geographical archipelagos. From northeast to southwest:

- Okinawa Islands (沖縄諸島, Okinawa-shotō)

- Iejima (伊江島, Iejima)

- Kume-jima (久米島町, Kumejima-chō)

- Okinawa Island (沖縄島, Okinawa-jima)

- Kerama Islands (慶良間諸島, Kerama-shotō)

- Miyako Islands (宮古列島, Miyako-rettō)

- Miyako-jima (宮古島, Miyako-jima)

- Yaeyama Islands (八重山列島, Yaeyama-rettō)

- Iriomote Island (西表島, Iriomote-jima)

- Ishigaki Island (石垣島, Ishigaki-jima)

- Yonaguni (与那国島, Yonaguni-jima)

- Senkaku Islands (尖閣諸島, Senkaku-shotō)

- Daitō Islands (大東諸島, Daitō-shotō)

- Minamidaitōjima (南大東島, Minami-Daitō)

- Kitadaitōjima (北大東島, Kita-Daitō)

- Okidaitōjima (沖大東島, Oki-Daitō)

Natural parks

[edit]Approximately 36% percent of the total land area of the prefecture was designated as natural parks, namely the Iriomote-Ishigaki, Kerama Shotō, and Yambaru National Parks; Okinawa Kaigan and Okinawa Senseki Quasi-National Parks; and Irabu, Kumejima, Tarama, and Tonaki Prefectural Natural Parks.[66]

Ecology

[edit]The dugong is an endangered marine mammal related to the manatee.[67] Iriomote is home to one of the world's rarest and most endangered cat species, the Iriomote cat. The region is also home to at least one endemic pit viper, Trimeresurus elegans. The islands of Okinawa are surrounded by some of the most abundant coral reefs found in the world.[68][69] The world's largest colony of rare blue coral is found off Ishigaki Island.[70] The sea turtles return yearly to the southern islands of Okinawa to lay their eggs. The summer months carry warnings to swimmers regarding venomous jellyfish and other dangerous sea creatures.

Okinawa is a major producer of sugar cane, pineapple, papaya, and other tropical fruit, and the Southeast Botanical Gardens represent tropical plant species.

Geology

[edit]The island is largely composed of coral, and rainwater filtering through that coral has given the island many caves, which played an important role in the Battle of Okinawa. Gyokusendo[71] is an extensive limestone cave in the southern part of Okinawa's main island.

Climate

[edit]The island experiences temperatures above 20 °C (68 °F) for most of the year. The climate of the islands ranges from humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) in the north, such as Okinawa Island, to tropical rainforest climate (Köppen climate classification Af) in the south such as Iriomote Island. Snowfall is unheard of at sea level. However, on January 24, 2016, sleet was reported in Nago for the first time on record.[72]

Politics

[edit]

Due to its unique historical background, Okinawa has a significantly stronger progressive (left-wing) presence compared to most other Japanese prefectures, making it one of the most politically polarized regions in the country. The Okinawa Social Mass Party, a local progressive political party, has played an important role in postwar Okinawan politics.[73]: 55–71

In 2014, various progressive parties such as the Social Democratic Party, Japanese Communist Party, Democratic Party, and the Okinawa Social Mass Party formed a cross-party electoral alliance with some conservative figures who also opposed the relocation of the U.S. Marine Corps Air Station Futenma to the city of Nago. This movement, known as the "All-Okinawa" campaign, achieved electoral victories in the 2014 Okinawa gubernatorial election,[74] the 2016 Okinawa prefectural election,[75] and others.

Since Japan introduced the Single-member district system in 1996, Okinawa has been divided into four electoral districts for the House of Representatives.[76] Among these, Okinawa's 2nd District, which hosts the highest concentration of U.S. military bases, has long been a stronghold for the progressive camp. Kantoku Teruya of the Social Democratic Party held this seat from 2003 onwards. The other three districts have seen fierce competition between conservatives and progressives, with frequent changes in party control.

In the 2014 Japanese general election, all four Okinawan districts elected candidates opposed to the relocation of the Futenma base to Nago. In the 1st District, Seiken Akamine of the Japanese Communist Party won a seat—marking the JCP’s first single-member district victory in Okinawa and its first nationwide in 18 years.[77]

In the 2017 Japanese general election, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) won the seat in the 4th District.[78] In the 2021 Japanese general election, LDP candidates won in both the 3rd and 4th Districts and also gained proportional representation seats in the 1st and 2nd Districts. The Japanese Communist Party and the Social Democratic Party each retained one seat.[79]

In the House of Councillors, Okinawa is represented by two seats in a single at-large district. Both are currently held by politicians who oppose the Futenma base relocation.[80] However, in proportional representation voting, the LDP has consistently received the highest number of votes in Okinawa.[81]

Okinawa has also experienced multiple changes in political leadership throughout its gubernatorial history.[82] In 2014, Takeshi Onaga, backed by progressive forces, was elected governor of Okinawa Prefecture.[83] After Onaga's death in 2018, another progressive candidate, Denny Tamaki, was elected governor in the September 2018 election.[84] Tamaki was re-elected in 2022.[85] However, in recent years, rising tensions across the Taiwan Strait have led to growing unease among Okinawans toward the People’s Republic of China, resulting in a loss of momentum for progressive forces.[86]

The Okinawa Prefectural Assembly consists of 48 members, with the Liberal Democratic Party holding the largest number of seats at 22.[87]

In terms of administrative jurisdiction, the disputed Senkaku Islands (referred to by China and Taiwan as the Diaoyu Islands) are administered by the city of Ishigaki in Okinawa Prefecture.[88]

According to a 2015 Okinawa Prefectural Government survey, only 9.3% of Okinawans felt an affinity toward the People’s Republic of China, while 88.1% did not. Similarly, 90.8% of respondents reported a negative impression of China.[89]

There is also a social and psychological divide between Okinawa and mainland Japan. In 2016, police officers from Osaka deployed to Okinawa for U.S. base security duties were recorded referring to protesters using discriminatory terms such as "dojin" (a derogatory word meaning "savage"), sparking widespread public criticism.[90]

A 2017 NHK survey found that only 19% of Okinawans believed mainland Japanese people understood their feelings, while 79.6% thought otherwise. Additionally, 56.9% felt that discrimination or defamation against Okinawa had increased over the previous five years.[91] Conversely, Okinawa itself has also faced issues of discrimination against Amerasian (U.S.–Japanese mixed-race) residents.[92]

Okinawa faces chronic fiscal challenges and relies heavily on subsidies from Japan’s central government. Its fiscal capacity index is only 0.29—significantly below the national average.[93]

U.S. Military Bases

[edit]

Although some land used by U.S. military bases has been returned to Japan since Okinawa reverted to Japanese control,[94]: 595 a significant portion remains under American jurisdiction. While Okinawa comprises only 0.6% of Japan’s land area, it hosts approximately 74% of all U.S. military facilities in the country.[95] The 33 American bases in Okinawa occupy around 10% of the prefecture's land—up to 18% on Okinawa Island.[96] Approximately 47,300 U.S. military personnel and their families reside in the prefecture.[97]

Among the many military issues, the relocation of Marine Corps Air Station Futenma has been the most contentious. Due to its proximity to residential areas and repeated accidents, Futenma has been labeled one of the most dangerous military bases in the world. The prefectural government has long called for its relocation outside of Okinawa.[98] In 2010, Japan and the U.S. agreed to relocate the base to Camp Schwab in Nago,[99] sparking widespread protests.

Another key issue is crime involving U.S. military personnel. Between the 1972 reversion and 2015, 5,896 criminal cases involving U.S. forces were reported in Okinawa.[100] In 2016, a high-profile rape and murder case involving a U.S. military contractor in Uruma triggered mass protests.[101]

On the other hand, U.S. bases are Okinawa's second-largest source of employment.[102][103]

According to a 2017 NHK survey, 25.7% of Okinawans wanted the complete removal of U.S. military bases, while 50.6% preferred reducing their presence to levels comparable to mainland Japan. Only 26.5% supported relocating Futenma to Nago, while 62.6% were opposed.[91] According to a 2015 prefectural survey, 42.2% of Okinawans reported no affinity toward the U.S., while 55.4% did.[89]

On February 24, 2019, a prefectural referendum was held on land reclamation in Henoko for the new U.S. base. With a turnout of 52.48%, 71.74% opposed the project, 18.99% supported it, and 8.70% expressed no clear opinion.[104]

Independence Movement

[edit]

After Japan officially annexed the Ryukyu Kingdom in 1879, the last Ryukyuan king, Shō Tai, was forced to relocate to Tokyo. Many Ryukyuans dissatisfied with Japanese rule fled to Qing China, where they became known as the Tatsuqingjin (脱清人). This movement, part of what is known as the “Second Ryukyu Disposition,” established bases in Fuzhou, Beijing, and Tianjin, petitioning the Qing court to intervene with Japan. This became known historically as the Ryukyu Dispute.[105]

Though some Qing and American officials proposed restoring the Ryukyu Kingdom, the idea was ultimately rejected due to conditions that would have required ceding large parts of Ryukyu territory to Japan. King Shō Tai and the Ryukyuan nobility opposed such proposals. After China's defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War, the Qing was no longer in a position to support Ryukyuan independence.[106] Shō Tai’s sons, Shō In and Shō Jun, led the Kyūdōkai movement advocating for a semi-autonomous Ryukyuan province within Japan, but this movement also failed. The death of King Shō Tai in 1901 further weakened historical ties to the former kingdom.[107]

The modern Ryukyuan independence movement emerged primarily after the end of the Pacific War in 1945. Some ethnic Ryukyuans believed that the Allied powers should help restore Ryukyuan sovereignty rather than return the islands to Japan. Left-wing Japanese parties, including the Japanese Communist Party and Japan Socialist Party, initially supported Ryukyuan independence.[108] However, amid the Cold War and following the defeat of China’s Nationalist government in the Chinese Civil War, the United States rejected independence and imposed strict control over Okinawa. Under the terms of the 1971 Okinawa Reversion Agreement, the islands were returned to Japan on May 15, 1972. The earlier U.S.–Japan Security Treaty allowed continued U.S. military presence in Okinawa, which laid the groundwork for a new phase of political radicalism supporting independence.

Independence advocates argue that both the 1609 Satsuma invasion of Ryukyu and the Meiji annexation of Okinawa constituted colonial occupations. They denounce the historical and ongoing treatment of the Ryukyuan people, especially the use of Okinawan land for large-scale U.S. military bases.[109]

In recent years, calls for greater autonomy—or even independence—have entered mainstream political discourse.[110][111] Ethnic and nationalist tensions between Okinawans and mainland Japanese are occasionally visible. Okinawans often refer to themselves as "Okinawans" and call mainland Japanese "Yamato people," while some mainlanders have used derogatory terms such as "dojin" (primitive native) or even "Chinese" to describe Okinawans.[112]

Historically, the Ryukyu Islands have maintained strong cultural and diplomatic ties with China. While the People's Republic of China has not officially challenged Japan’s sovereignty over Okinawa, and Chinese maps and documents list the islands as Japanese territory,[113] unofficial voices and scholars in China occasionally revisit the issue amid strained Sino-Japanese relations.[114][115][116]

Despite the visibility of independence activism, support for full independence remains marginal. A 2022 Okinawa Times survey found that only 3% of residents supported independence, while 48% favored a more autonomous local government, and 42% preferred maintaining the status quo.[117]

Municipalities

[edit]Cities

[edit]

City Town Village

Eleven cities are located within the Okinawa Prefecture:

| Name | Area (km2) | Population | Map | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rōmaji | Kanji | Okinawan[118] | other languages [script]

(name in brackets) | ||||

| Kana | Rōmaji | ||||||

| 宜野湾市 | じのーん | Jinōn | 19.51 | 94,405 | |||

| 石垣市 | いしがち | ʔIshigaci | Isïgaksï, Ishanagzï (Yaeyama) | 229 | 47,562 | ||

| 糸満市 | いちゅまん | ʔIcuman | 46.63 | 59,605 | |||

| 宮古島市 | なーく、みゃーく | Nāku, Myāku | Myaaku (Miyakoan) | 204.54 | 54,908 | ||

| 名護市 | なぐ | Nagu | Naguu [ナグー] (Kunigami) | 210.37 | 61,659 | ||

| 那覇市 | な |

Nafa | 39.98 | 317,405 | |||

| 南城市 | Fēgusiku | 49.69 | 41,305 | ||||

| 沖縄市 | うちなー | ʔUcinā | 49 | 138,431 | |||

| 豊見城市 | Timigusiku | 19.6 | 61,613 | ||||

| 浦添市 | うら |

ʔUrasī | 19.09 | 113,992 | |||

| うるま市 | うるま | ʔUruma | 86 | 118,330 | |||

Towns and villages

[edit]These are the towns and villages in each district:

| Name | Area (km2) | Population | District | Type | Map | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rōmaji | Kanji | Okinawan[118] | other languages [script]

(name in brackets) | ||||||

| Kana | Rōmaji | ||||||||

| 粟国村 | あぐに | ʔAguni | 7.63 | 772 | Shimajiri District | Village | |||

| 北谷町 | ちゃたん | Catan | 13.62 | 28,578 | Nakagami District | Town | |||

| 宜野座村 | じぬざ | Jinuza | 31.28 | 5,544 | Kunigami District | Village | |||

| 南風原町 | Fēbaru | 10.72 | 37,874 | Shimajiri District | Town | ||||

| 東村 | Figashi | Agaarijimaa [アガーリジマー]

(Kunigami) |

81.79 | 1,683 | Kunigami District | Village | |||

| 伊江村 | いい | ʔIi | Ii [イー] (Kunigami) | 22.75 | 4,192 | Kunigami District | Village | ||

| 伊平屋村 | いひゃ、後地 | ʔIhya, Kushijī | 21.72 | 1,214 | Shimajiri District | Village | |||

| 伊是名村 | いじな、前地 | ʔIjina, Mējī | 15.42 | 1,518 | Shimajiri District | Village | |||

| 嘉手納町 | か |

Kadinā | 15.04 | 13,671 | Nakagami District | Town | |||

| 金武町 | ちん | Cin | Chin [チン] (Kunigami) | 37.57 | 11,259 | Kunigami District | Town | ||

| 北大東村 | うふあがりじま | ʔUhuʔagarijima | 13.1 | 615 | Shimajiri District | Village | |||

| 北中城村 | にしなかーぐ |

Nishinakāgusiku | 11.53 | 16,040 | Nakagami District | Village | |||

| 久米島町 | くみじま | Kumijima | 63.5 | 7,647 | Shimajiri District | Town | |||

| 国頭村 | くんじゃん | Kunjan | Kunzan (Kunigami) | 194.8 | 4,908 | Kunigami District | Village | ||

| 南大東村 | Hwēʔuhuʔagarijima | 30.57 | 1,418 | Shimajiri District | Village | ||||

| 本部町 | む |

Mutubu | Mutubu (Kunigami) | 54.3 | 13,441 | Kunigami District | Town | ||

| 中城村 | なかーぐ |

Nakāgusiku | 15.46 | 20,030 | Nakagami District | Village | |||

| 今帰仁村 | なちじん | Nacijin | Nachizin (Kunigami) | 39.87 | 9,529 | Kunigami District | Village | ||

| 西原町 | にしばる | Nishibaru | 15.84 | 34,463 | Nakagami District | Town | |||

| 大宜味村 | Ujimi | Uujimii (Kunigami) | 63.12 | 3,024 | Kunigami District | Village | |||

| 恩納村 | うんな | ʔUnna | Unna (Kunigami) | 50.77 | 10,443 | Kunigami District | Village | ||

| 多良間村 | たらま | Tarama | Tarama (Miyakoan) | 21.91 | 1,194 | Miyako District | Village | ||

| 竹富町 | だき |

Dakidun | Teedun (Yaeyama) | 334.02 | 4,050 | Yaeyama District | Town | ||

| 渡嘉敷村 | Tukashici | 19.18 | 697 | Shimajiri District | Village | ||||

| 渡名喜村 | Tunaci | 3.74 | 406 | Shimajiri District | Village | ||||

| 八重瀬町 | え゙ー |

Ēsi | 26.9 | 29,488 | Shimajiri District | Town | |||

| 読谷村 | Yuntan | 35.17 | 40,517 | Nakagami District | Village | ||||

| 与那原町 | Yunabaru | 5.18 | 18,410 | Shimajiri District | Town | ||||

| 与那国町 | Yunaguni | Dunan, Juni (Yonaguni)

Yunoon (Yaeyama) |

28.95 | 2,048 | Yaeyama District | Town | |||

| 座間味村 | ざまみ | Zamami | 16.74 | 924 | Shimajiri District | Village | |||

Town mergers

[edit]Demography

[edit]

Ethnic groups

[edit]The indigenous Ryukyuans make up the majority of Okinawa Prefecture's population and are also the main ethnic group of the Amami Islands to the north. Large Okinawan diaspora communities persist in places such as South America[119] and Hawaii.[120] With the introduction of American military bases, there are an increasing number of half-American children in Okinawa, including prefecture governor Denny Tamaki.[121] The prefecture also has a sizable minority of Yamato people from mainland Japan; exact population numbers are difficult to establish, as the Japanese government does not officially recognize Ryukyuans as a distinct ethnic group from Yamatos.

The overall ethnic identity of Okinawa residents is rather split. According to a telephone poll conducted by Lim John Chuan-tiong (林泉忠), an associate professor with the University of the Ryukyus, 40.6% of respondents identified as "沖縄人 (Okinawan)", 21.3% identified as "日本人 (Japanese)" and 36.5% identified as both.[122][self-published source?]

Population

[edit]Okinawa prefecture age pyramid as of 1 October 2003[update][123]

(per thousands of people)

| Age | People |

|---|---|

| 0–4 | |

| 5–9 | |

| 10–14 | |

| 15–19 | |

| 20–24 | |

| 25–29 | |

| 30–34 | |

| 35–39 | |

| 40–44 | |

| 45–49 | |

| 50–54 | |

| 55–59 | |

| 60–64 | |

| 65–69 | |

| 70–74 | |

| 75–79 | |

| 80 + |

Okinawa Prefecture age pyramid, divided by sex, as of 1 October 2003[update]

(per thousands of people)

| Males | Age | Females |

|---|---|---|

| 43 |

0–4 | |

| 44 |

5–9 | |

| 45 |

10–14 | |

| 48 |

15–19 | |

| 46 |

20–24 | |

| 49 |

25–29 | |

| 49 |

30–34 | |

| 43 |

35–39 | |

| 46 |

40–44 | |

| 49 |

45–49 | |

| 52 |

50–54 | |

| 32 |

55–59 | |

| 32 |

60–64 | |

| 32 |

65–69 | |

| 24 |

70–74 | |

| 14 |

75–79 | |

| 17 |

80 + |

Per Japanese census data,[124][125] Okinawa prefecture has had continuous positive population growth since 1960.

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1873 | 166,789 | — |

| 1920 | 572,000 | +242.9% |

| 1930 | 578,000 | +1.0% |

| 1940 | 575,000 | −0.5% |

| 1950 | 915,000 | +59.1% |

| 1960 | 883,000 | −3.5% |

| 1970 | 945,000 | +7.0% |

| 1980 | 1,107,000 | +17.1% |

| 1990 | 1,222,000 | +10.4% |

| 2000 | 1,318,220 | +7.9% |

| 2010 | 1,392,818 | +5.7% |

| 2020 | 1,457,162 | +4.6% |

Language

[edit]There remain six Ryukyuan languages which, although related, are incomprehensible to speakers of Japanese. One of the Ryukyuan languages is spoken in Kagoshima Prefecture, rather than in Okinawa Prefecture. These languages are in decline as the younger generation of Okinawans uses Standard Japanese. Mainland Japanese and some Okinawans generally perceive the Ryukyuan languages as "dialects". Standard Japanese is almost always used in formal situations. In informal situations, de facto everyday language among Okinawans under age 60 is Okinawa-accented mainland Japanese ("Okinawan Japanese"), which is often mistaken by non-Okinawans as the Okinawan language proper. The actual traditional Okinawan language is still used in traditional cultural activities, such as folk music and folk dance. There is a radio-news program in the language as well.[126]

Culture

[edit]Okinawan culture retains strong influences from its historical trading partners. Among these, Kyushu has maintained the closest economic and cultural ties with Okinawa from ancient times to the present, and the two regions share many cultural traits. Elements of Okinawan culture can be found throughout Kyushu, and vice versa. For instance, Okinawan musical scales appear in Kyushu’s folk songs, and there are notable similarities in cuisine and language. Kyushu is also home to a traditional instrument called the gottan, which closely resembles the Okinawan sanshin.[127][128]

Furthermore, the customs of the Okinawan islands show strong influences from China, Thailand, and Austronesian-speaking regions. [129]

One of the most famous cultural traditions of Okinawa is undoubtedly karate. Karate is a martial art that originated when Chinese kung fu was introduced to the Ryukyu Kingdom and then developed independently within the islands before being brought to mainland Japan. Today, karate is practiced around the world in various styles, including Shotokan, Goju-ryu, Shito-ryu, and Uechi-ryu.[130]

A cultural feature of the Okinawans is the forming of moais. A moai is a community social gathering and groups that come together to provide financial and emotional support through emotional bonding, advice giving, and social funding. This provides a sense of security for the community members and as mentioned in the Blue Zone studies, may have been a contributing factor to the longevity of its people.[131] However, in recent decades Okinawans' life expectancy has fallen significantly (also bringing into question the general validity of the 'Blue Zones' denominaton), which often has been blamed on cultural influence from the rest of Japan, as well as foreign influences on Okinawans' lifestyle.[132]

Two Okinawan writers have received the Akutagawa Prize: Eiki Matayoshi in 1995 for The Pig's Retribution (豚の報い, Buta no mukui) and Shun Medoruma in 1997 for A Drop of Water (Suiteki). The prize was also won by Okinawans in 1967 by Tatsuhiro Oshiro for Cocktail Party (Kakuteru Pāti) and in 1971 by Mineo Higashi for Okinawan Boy (Okinawa no Shōnen).[133][134]

A traditional craft, the fabric named bingata, is made in workshops on the main island and elsewhere.

Music

[edit]

The music of the prefecture contains native and imported influences in both koten (classical) and min'yō (folk) styles. Okinawan instruments include the sanshin—a three-stringed banjo-like instrument, closely related to the Chinese sanxian, and ancestor of the Japanese shamisen. Its body is often bound with snakeskin (from pythons, imported from elsewhere in Asia, rather than from Okinawa's venomous habu, which are too small for this purpose). Okinawan musical cultures integrate dance with music, such as in eisa, a traditional drumming dance.[135]

Religion

[edit]Okinawan people have inherited a traditional religious belief system known as Ryukyuan Shinto, which is similar to but distinct from modern Japanese Shinto. This indigenous belief system is animistic in nature, characterized by ancestor worship and a deep respect for the relationships between the living, the dead, and the gods or spirits of the natural world.[136]

Shamanic practitioners, known as yuta, continue to play an active role in Okinawan society. They perform ritual prayers, divination, spiritual consultations, and even communicate with the spirits of the deceased. For many people, yuta serve as important spiritual guides who offer advice and solutions to both supernatural and everyday life problems.[137]

Throughout Okinawa, there are sacred sites known as utaki, where rituals and ceremonies are performed. Ryukyuan beliefs preserve many elements of ancient Japanese spirituality—such as those from the Jōmon and Yayoi periods—which have largely disappeared on the Japanese mainland. As such, they are considered important resources in comparative mythology and religious studies.[138][139]

Cuisine and diet

[edit]

The Okinawan diet consists of low-fat, low-salt foods, such as whole fruits and vegetables, legumes, tofu, and seaweed. Okinawans are particularly well known for consuming purple potatoes, also known as Okinawan sweet potatoes.[140] Okinawans used to be known for their longevity compared to the rest of Japan and the world in general. This particular island is a so-called Blue Zone, an area where people are purported to live longer than most others elsewhere in the world. Possible explanations for this were diet, low-stress lifestyle, caring community, activity, and spirituality of the inhabitants of the island.[141][page needed]

A traditional Okinawan product that owes its existence to Okinawa's trading history is awamori—an Okinawan distilled spirit made from indica rice imported from Thailand.

Architecture

[edit]

Despite widespread destruction during World War II, there are many remains of a unique type of castle or fortress known as gusuku; the most significant are inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List (Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu).[142] In addition, twenty-three Ryukyuan architectural complexes and forty historic sites have been designated for protection by the national government.[143] Shuri Castle in Naha is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Whereas most homes in Japan are made from wood and allow free-flow of air to combat humidity, typical modern homes in Okinawa are made from concrete with barred windows to protect from flying plant debris and to withstand regular typhoons. Roofs are designed with strong winds in mind, in which each tile is cemented on and not merely layered as seen with many homes in Japan.[citation needed] The Nakamura House (中村家住宅 (沖縄県) [ja]) is an original 18th century farmhouse in Kitanakagusuki. Many roofs also display a lion-dog statue, called a shisa, which is said to protect the home from danger. Roofs are typically red in color and are inspired by Chinese design.[144]

Education

[edit]The public schools in Okinawa are overseen by the Okinawa Prefectural Board of Education. The agency directly operates several public high schools[145] including Okinawa Shogaku High School. The U.S. Department of Defense Dependents Schools operates 13 schools total in Okinawa. Seven of these schools are located on Kadena Air Base.

Okinawa has many types of private schools. Some of them are cram schools, also known as juku. Others, such as Nova, solely teach language. There are 10 colleges/universities in Okinawa, including the University of the Ryukyus, the only national university in the prefecture, and the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology, a new international research institute. Okinawa's American military bases also host the Asian Division of the University of Maryland University College.

Sports

[edit]Martial arts

[edit]Martial arts, such as tegumi and Okinawan kobudō originated among the indigenous people of Okinawa Island. Due to its central location, Okinawa was influenced by various cultures including Japan, China and Southeast Asia in its martial arts culture.

Karate

[edit]

Karate originated in the Ryukyu Kingdom, under Chinese influence. Over time, it developed into several styles and sub-styles. On Okinawa, the three main styles are considered to be Shōrin-ryū, Gōjū-ryū and Uechi-ryū. Internationally, the various styles and sub-styles include Matsubayashi-ryū, Wadō-ryū, Isshin-ryū, Shōrinkan, Shotokan, Shitō-ryū, Shōrinjiryū Kenkōkan, Shorinjiryu Koshinkai, and Shōrinji-ryū.

Following Okinawa's occupation, karate spread to the United States and the rest of the world. It is now popular across the world, and has since been included in the Olympic Games.[146][147][148]

Association football

[edit]FC Ryukyu is a professional football team based on Okinawa. Since 2014 they have competed in the second or third tier in the national league system.

Basketball

[edit]

The Ryukyu Golden Kings are a professional basketball team that compete in the B.League, the top-tier professional basketball league of Japan. They are successful, having won the national title five times (most recently in 2023).

The Okinawa Arena has hosted the Japanese men's basketball team for various 2023 FIBA Basketball World Cup Asian qualifiers. It was also one of five venues to host the 2023 FIBA Basketball World Cup, the other four were in the Philippines and Indonesia.[149]

Handball

[edit]Baseball

[edit]In 2019, BASE Okinawa Baseball Club attempted forming the first-ever professional baseball team on Okinawa, the Ryukyu Blue Oceans. The team was expected to be fully organized by January 2020 with a view to joining the Nippon Professional Baseball league.[151]

However, complications arising from the COVID-19 pandemic compounded with allegations of financial mismanagement – including reports of unpaid wages to players – resulted in the project being put on hold in November of 2022. An exodus of players and staff followed, resulting in management company BASE officially filing for bankruptcy on April 6th, 2023.[152]

Despite the lack of a local team, various professional baseball teams hold winter training camps in Okinawa as it is the warmest prefecture of Japan, with no snow and higher average temperatures than other prefectures. In 2025, ten teams held such camps across the prefecture, including two teams from the KBO League.[153]

- Yomiuri Giants

- Hanshin Tigers

- Yokohama DeNA BayStars

- Hiroshima Toyo Carp

- Tokyo Yakult Swallows

- Chunichi Dragons

- Hokkaido Nippon-Ham Fighters

- Chiba Lotte Marines

- Samsung Lions (Korea)

- Doosan Bears (Korea)

Golf

[edit]There are numerous golf courses in the prefecture, and there was formerly a professional tournament called the Okinawa Open.

Transportation

[edit]Air transportation

[edit]- Aguni Airport

- Hateruma Airport

- Iejima Airport

- Kerama Airport

- Kitadaito Airport

- Kumejima Airport

- Minami-Daito Airport

- Miyako Airport

- Naha Airport

- New Ishigaki Airport

- Shimojishima Airport

- Tarama Airport

- Yonaguni Airport

Highways

[edit] Okinawa Expressway

Okinawa Expressway Naha Airport Expressway

Naha Airport Expressway National Route 58

National Route 58 National Route 329

National Route 329 National Route 330

National Route 330 National Route 331

National Route 331 National Route 332

National Route 332 National Route 390

National Route 390 National Route 449

National Route 449 National Route 505

National Route 505 National Route 507

National Route 507

Rail

[edit]Ports

[edit]The major ports of Okinawa include:

- Hirara Port[154]

- Port of Ishigaki[155]

- Port of Kinwan[156]

- Nakagusukuwan Port[157]

- Naha Port[158]

- Port of Unten[159]

Economy

[edit]The island economy is primarily driven by tourism and the U.S. military presence.[160] Other significant contributors to the economy include public utilities and public works, as well as, to a lesser extent, limestone mining, cement production, agriculture, telecommunications (Okinawa Cellular Telephone), and alcoholic beverage production (Orion Breweries).[161][162][163]

The 34 U.S. military installations on Okinawa are financially supported by the U.S. and Japan.[164] The bases provide jobs for Okinawans, both directly and indirectly; in 2011, the U.S. military employed over 9,800 Japanese workers in Okinawa.[164] As of 2012[update] the bases accounted for up to 5% of the economy.[165] However, Koji Taira argued in 1997 that because the U.S. bases occupy around 20% of Okinawa's land, they impose a deadweight loss of 15% on the Okinawan economy.[166] The Tokyo government also pays the prefectural government around ¥10 billion per year[164] in compensation for the American presence, including, for instance, rent paid by the Japanese government to the Okinawans on whose land American bases are situated.[167] A 2005 report by the U.S. Forces Japan Okinawa Area Field Office estimated that in 2003 the combined U.S. and Japanese base-related spending contributed $1.9 billion to the local economy.[168] On January 13, 2015, in response to the citizens electing governor Takeshi Onaga, the national government announced that Okinawa's funding will be cut, due to the governor's stance on removing the US military bases from Okinawa, which the national government does not want happening.[169][170]

The Okinawa Convention and Visitors Bureau is exploring the possibility of using facilities on the military bases for large-scale meetings, conferencing, exhibitions events.[171]

United States military installations

[edit]- United States Marine Corps

- Marine Corps Base Camp Smedley D. Butler

- Camp Courtney

- Camp Foster

- Camp Gonsalves (Jungle Warfare Training Center)

- Camp Hansen

- Camp Kinser

- Camp McTureous

- Camp Schwab

- Marine Corps Air Station Futenma

- Marine Corps Base Camp Smedley D. Butler

- United States Air Force

- United States Navy

- United States Army

Notable people

[edit]- Namie Amuro, hip hop and pop singer

- Yui Aragaki, actress, singer and model

- Awich, rapper, singer and songwriter

- Beni, pop and R&B singer

- Zach Bryan, country musician and singer-songwriter

- Michael Carter, National Football League player

- Isamu Chō, officer in the Imperial Japanese Army

- Merle Dandridge, American actress and singer

- Byron Fija, Okinawan language practitioner and activist

- Gichin Funakoshi, martial artist, founder of Shotokan

- Gigō Funakoshi, martial artist

- Gackt, pop rock singer-songwriter, actor and author

- Robert Griffin III, National Football League player, Heisman Trophy winner

- Hearts Grow, alternative rock band

- Takuji Iwasaki, meteorologist, biologist and ethnologist historian

- Eiki Matayoshi, novel writer, winner of Akutagawa prize

- Jin Matsuda, singer, member of INI

- Saori Minami, kayōkyoku pop singer

- Daichi Miura, pop singer, dancer and choreographer

- Chōjun Miyagi, martial artist, founder of Gōjū-ryū

- Yukie Nakama, singer, musician and actress

- Rino Nakasone, professional dancer and choreographer

- Rimi Natsukawa, pop singer

- Orange Range, rock band

- Minoru Ōta, admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy

- Dave Roberts, Major League Baseball player and manager

- Toshiyuki Sakuda, professional wrestler

- Eisaku Satō, politician, 61st, 62nd and 63rd Prime Minister of Japan

- Aisa Senda, singer, actress and TV presenter in Taiwan

- Ben Shepherd, bassist of Soundgarden

- Stereopony, all-female pop rock band

- Noriyuki Sugasawa, basketball player

- Super Shisa, professional wrestler

- Tina Tamashiro, fashion model and actress

- Yuken Teruya, interdisciplinary artist

- Tamlyn Tomita, actress and singer

- Kanbun Uechi, martial artist, founder of Uechi-ryū

- Mitsuru Ushijima, general at the Battle of Okinawa

- Kentsū Yabu, martial artist prominent in Shōrin-ryū

- Chikako Yamashiro, filmmaker and video artist

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "2020年度国民経済計算(2015年基準・2008SNA) : 経済社会総合研究所 – 内閣府". 内閣府ホームページ (in Japanese). Retrieved May 18, 2023.

- ^ "ちん【県・縣】: chin". JLect. Retrieved January 8, 2025.

- ^ Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Okinawa-shi" in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 746–747, p. 746, at Google Books

- ^ "沖縄の面積 (Okinawa's Area)" (in Japanese). Okinawa Prefecture. Archived from the original on August 16, 2020. Retrieved August 29, 2020.

- ^ "離島の概況について (Overview of Remote Islands)" (in Japanese). Okinawa Prefecture. Archived from the original on August 16, 2020. Retrieved August 29, 2020.

- ^ Nussbaum, "Naha" in p. 686, p. 686, at Google Books

- ^ 竹内理三 (1986). 角川日本地名大辞典 47 沖縄県 (Kadokawa Nihon Chimei Daijiten 47: Okinawa Prefecture) (in Japanese). Tokyo: 角川書店. ISBN 4-04-001470-7.

- ^ a b Lin, Man-houng. "The Ryukyus and Taiwan in the East Asian Seas: A Longue Durée Perspective", Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, October 27, 2006.

- ^ a b 竹内理三 (1986). 角川日本地名大辞典 47 沖縄県 (Kadokawa Nihon Chimei Daijiten 47: Okinawa Prefecture) (in Japanese). Tokyo: 角川書店. ISBN 4-04-001470-7.

- ^ Matsuo, Kanenori Sakon (2005). The Secret Royal Martial Arts of Ryukyu, p. 40, at Google Books

- ^ Inoue, Masamichi S. (2017), Okinawa and the U.S. Military: Identity Making in the Age of Globalization, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-51114-8, archived from the original on February 17, 2017, retrieved February 12, 2017

- ^ "U.S. civilian arrested in fresh Okinawa DUI case; man injured". The Japan Times. June 26, 2016. Archived from the original on July 31, 2017.

Under a decades-old security alliance, Okinawa hosts about 26,000 U.S. service personnel, more than half the total Washington keeps in all of Japan, in addition to base workers and family members.

- ^ "駐地基本資料 (Okinawa Basic Facts)". Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Office in Naha (in Chinese (Taiwan)). July 12, 2018. Archived from the original on September 26, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j 安里進, 高良倉吉, 田名真之, 豊見山和行, 西里喜行, 真栄平房昭 (2004). 沖縄県の歴史 (History of Okinawa Prefecture) (in Japanese). Tokyo: 山川出版社 (Yamakawa Publishing). ISBN 4-634-32470-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Excavation Report of the Sakitari Cave Site, Nanjo City, Okinawa" (PDF) (in Japanese). National Research Institute for Cultural Properties. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 29, 2020. Retrieved August 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar 新城俊昭 (2007). 琉球・沖縄史 (History of Ryukyu and Okinawa) (in Japanese). Okinawa: 東洋企画 (Toyo Planning). ISBN 978-4-938984-17-5.

- ^ "琉球王国とは". 首里城公園 Official Site (in Japanese). Retrieved April 12, 2025.

- ^ a b 金城正篤, 上原兼善, 秋山勝, 仲地哲夫, 大城将保 (2005). 沖縄県の百年 (One Hundred Years of Okinawa Prefecture) (in Japanese). Tokyo: 山川出版社 (Yamakawa Publishing). ISBN 4-634-27470-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The 10-10 Air Raid and the War in Naha City" (in Japanese). Naha City Education Institute. Archived from the original on August 24, 2020. Retrieved August 29, 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Hou, Yi (December 2015). "The Post-WWII Disposition of the Ryukyu Issue and the Origin of the Diaoyu Islands Dispute". China’s Borderland History and Geography Studies (in Chinese). 25 (4). Institute of Chinese Borderland Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences: 124–132.

- ^ a b An, Chengri; Li, Jinbo (December 2011). "On the Formation of U.S. Trusteeship Policy Over Okinawa After WWII (Part 1)". Journal of Beihua University (Social Science Edition) (in Chinese). 12 (6). Beihua University: 61–66.

- ^ "平和の礎(いしじ)". 沖縄県営平和祈念公園 (in Japanese). Retrieved April 12, 2025.

- ^ "Battle of Okinawa", Wikipedia, April 11, 2025, retrieved April 12, 2025

- ^ Special Subcommittee of the Armed Services Committee, House of Representatives (1955). "The Melvin Price Report". via Ryukyu-Okinawa History and Culture Website. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ Wampler, Robert A. (May 14, 1997). "Revelations in Newly Released Documents about U.S. Nuclear Weapons and Okinawa Fuel; NHK Documentary". George Washington University. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- ^ "Memorandum, Ambassador Brown to Secretary Rogers, 4/29/69, Subject: NSC Meeting April 30 – Policy Toward Japan: Briefing Memorandum (Secret), with attached". George Washington University. April 30, 1969. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 13, 2018. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- ^ "NSSM 5 – Japan, Table of Contents and Part III: Okinawa Reversion (Secret)". George Washington University. 1969. p. 22. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- ^ "Memorandum of Conversation, Nixon/Sato, 11/19/69 (Top Secret/Sensitive)". George Washington University. November 19, 1969. p. 2. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- ^ Journal, The Asia Pacific (January 7, 2013). ""Herbicide Stockpile" at Kadena Air Base, Okinawa: 1971 U.S. Army report on Agent Orange | The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus". apjjf.org. Archived from the original on August 16, 2020. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ Norris, Robert S.; Arkin, William M.; Burr, William (November 1999). "Where They Were" (PDF). Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 55 (6): 26–35. doi:10.2968/055006011. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 23, 2013.

- ^ Annie Jacobsen, "Surprise, Kill, Vanish: The Secret History of CIA Paramilitary Armies, Operators, and Assassins", (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2019), p. 102

- ^ John Morrocco. Rain of Fire. (United States: Boston Publishing Company), pg 14

- ^ a b Trumbull, Robert (August 1, 1965). "OKINAWA B-52'S ANGER JAPANESE: Bombing of Vietnam From Island Stirs Public Outcry". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ Mori, Kyozo, Two Ends of a Telescope Japanese and American Views of Okinawa, Japan Quarterly, 15:1 (1968:Jan./Mar.) p.17

- ^ a b Havens, T. R. H. (1987) Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965–1975. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Pg 120

- ^ Havens, T. R. H. (1987) Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965–1975. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Pg 123

- ^ Christopher T. Sanders (2000) America's Overseas Garrisons the Leasehold Empire Oxford University Press PG 164

- ^ Havens, T. R. H. (1987) Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965–1975. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press Pg 88

- ^ a b Rabson, Steve. "Okinawa's Henoko was a 'Storage Location' for Nuclear Weapons: Published Accounts". The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. 11 (1(6)). Archived from the original on February 13, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ^ States, United (1973). Reversion to Japan of the Ryukyu and Daito Islands, official text. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- ^ "US soldier charged in Okinawa for rape of minor". www.bbc.com. June 26, 2024. Retrieved April 12, 2025.

- ^ Johnston, Eric (May 15, 2002). "Nuclear pact ensured smooth Okinawa reversion". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011.

- ^ 疑惑が晴れるのはいつか(in Japanese), Okinawa Times, May 16, 1999

- ^ a b "No home where the dugong roam". The Economist. October 27, 2005. Archived from the original on September 5, 2006. Retrieved September 7, 2006.

some of the bloodiest campaigns anywhere in the second world war were fought in Okinawa, and a third of the civilian population died.

- ^ a b 沖縄に所在する在日米軍施設・区域 Archived October 1, 2007, at the Wayback Machine(in Japanese), Japan Ministry of Defense

- ^ [https://web.archive.org/web/20100523062343/http://www.asahi.com/politics/update/0513/SEB201005130037.html "asahi.com��ī����ʹ�ҡˡ���ŷ�ְ��������ˡ���̱������ȿ�С�ī����ʹ����Ĵ�� - ����"]. May 23, 2010. Archived from the original on May 23, 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2025.

{{cite web}}: replacement character in|title=at position 10 (help) - ^ McCurry, Justin (February 28, 2008). "Rice says sorry for US troop behaviour on Okinawa as crimes shake alliance with Japan". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ^ Hassett, Michael (February 26, 2008). "U.S. military crime: SOFA so good?The stats offer some surprises in wake of the latest Okinawa rape claim". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on March 5, 2008.

- ^ "Okinawa: Effects of long-term US Military presence" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 26, 2011. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- ^ Hearst, David (March 11, 2011). "Second battle of Okinawa looms as China's naval ambition grows". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on August 1, 2016. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ^ "米国海兵隊: 品位と名誉の精神" (PDF). Marine Corps Installations Pacific Ethos Data. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 23, 2016.

- ^ Pomfret, John (April 24, 2010). "Japan moves to settle dispute with U.S. over Okinawa base relocation". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 29, 2018. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ Cox, Rupert (December 1, 2010). "The Sound of Freedom: US Military Aircraft Noise in Okinawa, Japan". Anthropology News. 51 (9): 13–14. doi:10.1111/j.1556-3502.2010.51913.x. ISSN 1556-3502. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ^ Jon Mitchell, "Agent Orange on Okinawa – The Smoking Gun: U.S. army report, photographs show 25,000 barrels on island in early '70s" Archived January 23, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol 11, Issue 1, No. 6, January 14, 2012.

- ^ Jon Mitchell, "Were U.S marines used as guinea pigs on Okinawa?" Archived February 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol 10, Issue 51, No. 2, December 17, 2012.

- ^ Denyer, Simon (September 30, 2018). "Opponent of U.S. Military bases wins Okinawa gubernatorial election". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 17, 2019. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ Steven Donald Smith (April 26, 2006). "Eight Thousand U.S. Marines to Move From Okinawa to Guam". American Forces Press Service. DOD. Archived from the original on September 24, 2014. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- ^ "U.S., Japan unveil revised plan for Okinawa". Reuters. April 27, 2012. Archived from the original on June 20, 2012. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ "A closer look at U.S. Futenma base's 'relocation' issue". Japan Press Weekly. November 1, 2009. Archived from the original on November 13, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- ^ Mitchell, Jon (August 19, 2012). "Rumbles in the jungle". The Japan Times Online. Archived from the original on September 10, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- ^ Garamone, Jim (December 21, 2016). "U.S. Returns 10,000 Acres of Okinawan Training Area to Japan". U.S. Department of Defense. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2016.